Madness, Rack, and Honey

Mary Ruefle’s collection of essays, Madness, Rack, and Honey, weaves together the strange appeal of writing and art. She articulates the mystery and charm of poetry, acknowledging that it boils down to writing what inspires madness, rack, and honey in all of us. As artists, we are drawn to what pushes us into the brinks of wilderness, what torments us, and what softens our minds and souls. Ruefle’s words are also an apt description for the following short story writers, poets, and artists, whose works are utterly uninhibited and honest. We hope you’ll enjoy this issue of Adsum Magazine.

Emily Browne

Home

Driving down the high

Ways and ways away from my

Homemade picture frames packed in my

Bagpipes? Why is that on the

Radiologists said I have a

Yearning for your touch has driven me

Madagascar is a place I should go before I

Dieting has been a waste of

Timeouts are not allowed in this

Gamey meat when I was young always tasted like

Dirty hands and feet played all day in the

Sunsets and s’mores on the beach for every birthday

Parties in high school are where I got into some

Trouble-making, money-taking, misbehaving

Teenage pregnancies always scared me

Most of my life I’ve lived in

Fearful people at church pray for my dear

Soulful music didn’t pray but

Swear to me you’ll never leave Mommy

Please I need you in my

Lifetime movie marathons and a cup of

Tears streaming down my face for no

Reasons why I left, I thought, were unselfish and

Kindred spirits are meant to be together so I am coming Home

Jean Frazier

Sunday Mornings

On Sunday mornings, I didn’t go to church like the other kids in my neighborhood. Sarah from next door, Kelly from down the block, would leave their houses in bright, flowy dresses, while I would walk out the front door in ripped jeans and a windbreaker that smelled like mothballs, my hair covered beneath an old baseball cap.

Mom didn’t like it. She wasn’t religious, but she cared what people thought.

Every Saturday night during dinner, after she had spooned a few scoops of hotdish composed of that week’s leftovers (almost always involving some kind of meat and cream of mushroom soup) onto my and Dad’s plates, she would smooth a paper napkin across her lap and ask what our plans for tomorrow were. Dad, chewing slowly and not looking at her, would say, Dammit, Linda, can we not? and Mom would slam her silverware down. What? Am I not allowed to ask a question?

They’d go back and forth for a while—Mom saying that it was weird, that the other moms were always whispering about her during PTA meetings, that it wasn’t healthy for me to be different at such a young age; Dad rolling his eyes and telling her that she was being paranoid, no one cared, being out in the fresh and the air was good for me. They’d eat and argue in strained tones, struggling to be civil, about what was proper and right and I would sit between them, not eating and wondering whether they’d even notice if I just got up and left. There were books I wanted to read that I got from Mr. Paulson’s rummage sale last week sitting on my bed, their thickness and lack of pictures both exciting and terrifying. Champ was outside; I’m sure I would’ve been happier chasing squirrels and rolling around in the grass with him.

After our plates were cleared and Mom had gone to her room to be alone and Dad had sunk into the couch to drink and watch the Vikings lose, I’d still be sitting at the table tracing invisible patterns into the tablecloth with my fingers and thinking about what Saturday dinner would be like if I wasn’t there. I’d draw horses and stars and imagine a world where Mom and Dad could have dinner and not fight, just eat and smile and love. I’d be this close to slipping out the back door, already knowing which sweater I would pull on, which CD I would shove into my Walkman, and which city I would walk to—sometimes Minneapolis, or San Francisco, or Paris, but usually Rose Hill, North Carolina (I liked the way that people in the South talked and I wanted to see how many eggs could fit in the world’s largest frying pan).

But before I could double-knot my sneakers, Dad would finish his fourth beer and go into the kitchen where Mom was washing the dishes and hug her from behind, extra long and tight. There were never any I’m sorry’s or I love you’s. She would make him promise to be back in time to shower and change before dinner, he’d kiss her on the cheek, and then it would be okay, over and forgiven until next Saturday night. He’d let her go and then pick me up, hoisting me on his shoulders and spinning me around in circles until I felt sick, but happy.

On Sunday mornings, as I waited on the front doorstep for Dad to be ready, I’d watch Sarah and Kelly and all the other pretty little girls walk by in shiny, giggly clusters, trying to decide if I wanted them to notice me or not. I was fascinated by how effortlessly they walked in such uncomfortable shoes and wondered if it was skill they all had individually, intrinsically, or if it was something that only came about when they were together. When I was the flower girl at my cousin Tommy’s wedding, I walked down the aisle with a bouquet of tulips and daisies, crying, my feet rubbing painfully against the walls of my heels. Mom was so mad that afterwards at the reception, I didn’t get to have any cake. Maybe Sarah’s and Kelly’s and the other pretty little girls’ feet hurt as badly as mine did; they just knew how to hide it better.

Dad would come out the front door, his hair still damp from the shower, with a cooler and poles in one hand, and a mug of what looked like coffee, but smelled like something deeper and darker in the other. You get everything set up? I’d look up at him and nod, squinting against the sunlight that was able to sneak its way past his tall, bulky form. Did you fill up the tank? Do we have enough night crawlers? Is my lucky dardevle in the tackle box? I’d nod, nod, and nod, and then he’d grin and nod back at me, like I’d done good. Well, then what are we waiting for, tater-tot? His smile would be so big and the air would taste so clean that I wouldn’t even mind when every few steps he’d stumble and slosh a little of the weird-smelling coffee on my jacket.

In twenty minutes we’d be out on the lake, the boat’s engine groaning and coughing up exhaust as we cut through the water, my face being kissed by wind and spray. At the center of the lake—Dad always somehow knew when we reached the center—he’d stop the engine, drop the anchor. The sun would be at its highest point and the lake’s face would be in patches invitingly blue, and in others, hard to stare at for more than a few seconds, the light reflecting off it too bright.

Dad would have to bait my line for me. Even though they were just worms and according to him, didn’t have a favorite color or a song that made their eyes cloudy when it came on the radio or memories of their mommies and daddies, my chest still got tight whenever I tried to pierce their slimy skins with the tip of my hook. You’re being ridiculous, he’d say. They’re worms, they don’t feel pain. But the way they’d shrink away and squirm in my hands as I wedged my hook through them, made it hard for me to believe that that was true; their blood was just as red as mine. We always let go of whatever we caught—it was my favorite part: grabbing the slippery underbelly of the fish, hurling it back into the lake, and imagining how great that first gulp of water must taste to them—but for the worms, there was nothing; a few moments of quiet, underwater serenity before they were nibbled apart. When Dad would finish sealing the worm’s fate on my pole, I’d try not to look down, but out at the water instead.

After he was done helping me, he would grab his pole and pull a beer from the cooler. He’d take a long sip and when he’d finish, foam in his beard, he’d say that he felt God in the lake breeze more than when he prayed in a stuffy room filled with guilty, Hell-fearing people. He’d cast out with a grace that never failed to stun me—it was like if you were at the zoo and all of a sudden the elephant started dancing ballet, pirouetting around its cage—and when his moment of elephant grace was over, he’d sit down, leaning forward and rubbing his hands together, slowly, repeatedly. Can you hear that? Can you hear that? he’d ask me, eyes brown and blazing. I never knew what he was hearing exactly, but I liked to smile and pretend that I did. He’d open another beer and offer me one too and I’d take it, but not drink it—I didn’t like how it tasted, only how the icy can felt against my cheek.

I’d grab my pole and cast out as far as I could and when my line would come back down to Earth, landing with a soft satisfying plop, I’d close my eyes and try to feel something—maybe God, maybe not—in the lake breeze too.

Stephanie Chen

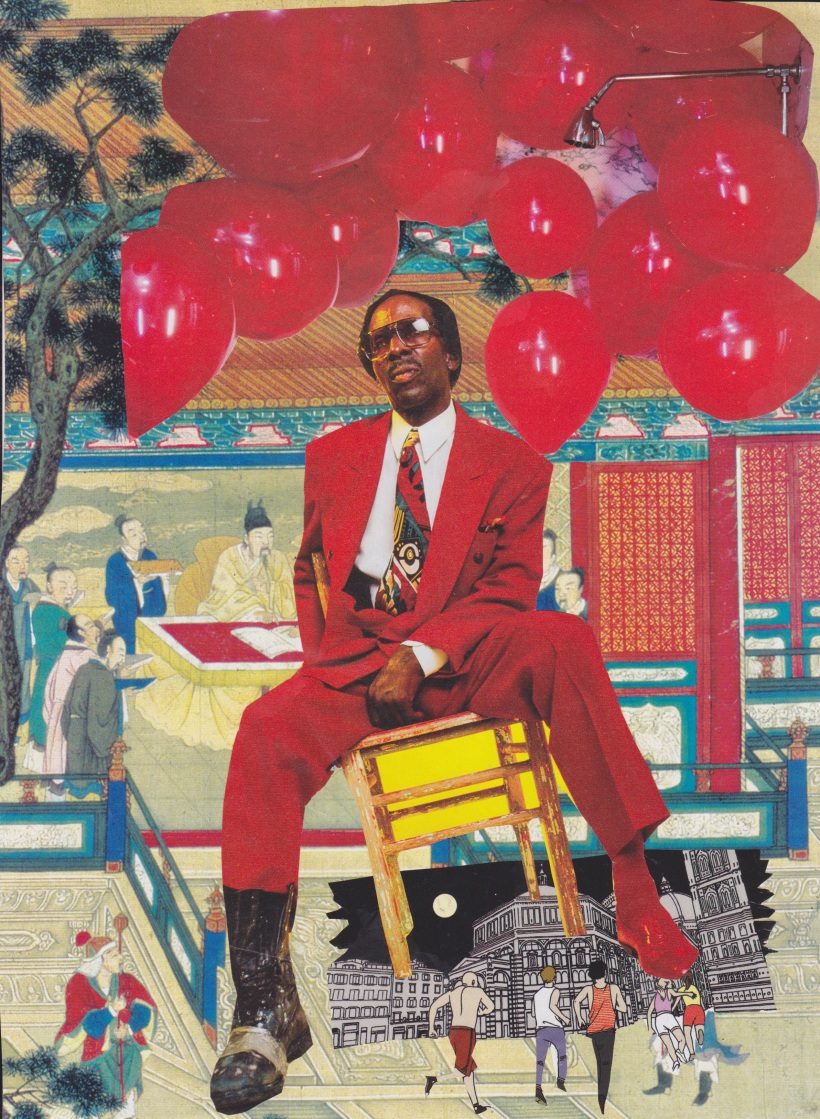

Claire Dougherty

Counterfeit

Forget what your mother said.

You can buy a record player with your good looks.

Unless it is a state of the art record player

in which case I would say

have your sister purchase it with her better looks

and then trade her later,

unless she desires something of equal value

which you cannot afford with your mediocre looks

in which case I would say

have you tried garage sales?

Assuming that attractiveness is the currency here

and in this economy you are broke,

it is difficult to objectify,

and thus to quantify,

allowing one of lesser income

could get by.

You see, everyone is a criminal in this economy,

and there are countless methods of counterfeit,

such as,

have you tried makeup?

such as lipstick or blush?

Brushing your hair,

for example?

Or if all else fails,

large dark sunglasses?

Better yet

order your purchases from the internet,

where your face can be posed

in such a way

as to appear wealthier

than it otherwise may

in a natural light,

and photoshop for those who know how to do it right

can be a powerful tool for hustling.

Youʼll be safe

so long as you can impersonate,

and the only thing that might give you away

is your debt from years of recession,

because who wants to transact

with a girl in depression?

In which case I would say

here is another opportunity for fraudulence.

Seeing as you are a poor girl

trying to be well off,

you must maintain it, your counterfeit,

by smiling

and forging positivity,

hiding the baggage that would expose

your felony.

Unless you have an unfortunate smile

(such as yellow or missing teeth)

in which case I would say

donʼt

and maybe just nod politely.

And if you are prone

to revealing negativity,

I would advise that you keep away

from notoriously positive places,

such as parks, for example,

or ice skating rinks,

beaches with tan faces

and white teeth,

unless you can find an inexplicable sadness

in otherwise happily seeming strangers,

to ease your own deficit,

in which case I would say

go for it,

but also why are you so mean?

Pretty girls arenʼt mean.

Your meanness may be detected

and your counterfeit defected

in which case I would say

hide,

because your bent cards will be on the table

and your hand will be poorer than ever

and youʼll have nothing but a broken record player

purchased at a garage sale.

Patrick Cleland

The Occupation (Villanelle for Jackson)

The fleeting feeling comes and goes in waves.

The undertow could pull at any time;

It occupies, but rarely ever stays.

Don’t think about sons lying in fresh-laid graves—

Life is jail—death’s freedom forgets all crime.

The fleeting feeling comes and goes in waves.

As we grasp for answers in the following days,

Shallow confusion gives way to the sublime.

It occupies, but rarely ever stays.

Don’t think about ways we could have split or saved

The strength of his body from the disease of his mind.

The fleeting feeling comes and goes in waves.

The grieving mother beneath cold earth lays

The empty vessel once filled by a friend of mine.

It occupies, but rarely ever stays.

Far from God’s plan, yet in an predestined way

His body descends and soul softly climbs.

A fleeting friend came, and goes today.

He occupied, but decided not to stay.

Cliff Weber

Emily Browne

Buoys

It’s easy to sink when the water is already over your head.

Letting out small bubbles determined to find where they came from

Small buoys desperate to find the surface.

This is how we are trained, you see.

We enter the water to save a life that tries to take ours

They thrash and crash in the water like desperate bubbles

We are their buoys

So we sink to survive and resurface,

Controlled and calm,

Buoyant and brave.

As children we played on the buoys in the bay.

Summers of bay swims and beach days

Sunshine, sunscreen, and sunglasses.

We would swim to them and climb on them

Careful not to touch the moss, algae and slime clinging to the bottom.

We were thrown off when the buoy had had enough of us

Generations of children trying to do the impossible by sinking the buoy,

Our authority as beach rats

Our captain as a fleet of novices.

We were performance artists,

Flinging water on each other that left small rings of salt on our skin,

Making drip music in the outdoor showers,

And kissing strangers for the first time behind the bathroom under the stairs.

All of these made our hearts float to the surface

Bobbing and bowing in our chests with the flood of excitement.

We were buoys on land

Hoping it would last forever.

We were warned not to sink

Rock bottom was not somewhere where people like us go.

But looking up from below the surface,

We remember the days of summer,

Take a lesson from the buoys,

And Float.

Esmeralda Jimenez

I Lost It on a Tuesday

Too far removed. Eyes wash salt out only to run dry, ephemeral and inconsistent. Stomach feels the splash of a heart, the sound echoes and gurgles through her. Her skin creeps and prickles, an eternal frost lingers on it. She keeps shaking her head, back and forth, back and forth- repeats a single phrase, “This isn’t real.” Her dry eyes cannot blink and they eventually look glazed. She is absent of sound and presence. Her catatonic states in between brief clarity and between bookends of melancholia, run until they tire themselves. Sometimes she doesn’t even exhale.

Her vision seems false. The ends are crinkled like an old poster, merely mimicking real scenes, she senses this reality cannot be true. This world is not her world. A foreign entity, she stares at colors, impressed with the hue yet keenly aware they are artificial flavors. She continues repeating, “This isn’t real.”

He’s merely a spectator.

She merely needed a spectator. Talking to herself would be suspicious were it not for his body turned towards hers. She keeps murmuring truths under her breath, attempts to calm her charging mind. She fights the urge to turn it all off. Sparks of irrationality flit off her breath, filled with the scents of a runaway, with the fear of being caught. As fast as she is, as smart as she is, she’s not entirely sure what’s wrong.

It started with the deadlines. Well, let’s say it started there. In reality it probably started on a gravel road that she remembers falling on. She remembers shoes with pink bows and knees polluted with grey dust. In a photograph she found later, there are rows of hops reaching toward the sky.

It started with the deadlines creeping up. She sees them like objects in her peripheral vision. They are not yet materialized yet their force will be solid on impact. It was the work schedule pushing twenty hours a week. It was finding a flea infested kitten and fearing not just its death but its lack of life. It was coffee being spilled on the computer her father spent two weeks salary to pay for. It was knowing this man owed her nothing (she was once a kitten herself) and yet she could not pay in the currency of familial love because they did not share blood. It was fearing her sisters would never know happiness, her mother never trust, herself never truth. It was fearing she pressured the youngest, hung her with the burden of responsibility anchoring her to deep seas rather than encouraging flight. It’s the survivor’s guilt eating away at her, dissolving pieces and drenching her blood in shame for wanting so goddamn much, never giving enough, or appreciating the perspective from the middle of the ladder because shes too busy looking for the next rung.

It’s knowing she can afford to sit on her ass and critique the hipsters for gentrifying neighborhoods while going to a school enclosed with black fences that changes it’s flowers to fresh shades of cardinal and gold every two weeks. It’s knowing she can never share it all; the knowledge, the experience; it will all be diluted upon sharing.

It’s the tax deadline and wondering if she should try to collect the money from a fake social security number or it that’s just pushing it too far.

It’s the lack of sleep due to whitewater thoughts, coursing through channels of her mind, carving gullies where she drowns and tosses at night. It’s the comments about how many fucking music festivals she’s gone to, whose summer home lost property values once the storm hit, who gives a shit and who can pay someone else to give a shit for them. It’s the lack of depth, it’s the ache in between scapulas from carrying the spheres of so many others she wants to represent fairly. It’s the ticking clock. It’s the gypsy boy whispering tales of liberation and free love, never mentioning the four PhDs, and one real nice house in the suburbs of Cambridge.

It’s the “you have such a nice tan” from the white girls whos blonde locks she coveted at one point. It’s the spines she is ripping out from her very pores so she stops carrying around an armor tinged in resentment and dipped with sarcasm.

It’s missing truth. It’s missing the moment. It’s finding her missing mind, let alone missing a balanced one. It’s the mistakes and miscommunication.

It’s everything. It’s nothing. It’s one of those days, or maybe one of those years.

It’s having a gold name tag with the title “Dornsife Ambassador” and a slight tremor in her right hand while stumbling over answers to strangers she normally charms. It’s the parent after the presentation who asks her if her son will get into medical school, if this school is better than Dartmouth and the beat she did not wait on to frantically answer with, “One third of the global population lacks access to clean water. Your son is going to be fine. He’s fine. I know you’re worried but he’s fine.” It’s running away fully aware she’s gone mad. It’s trying to stutter it all out and explain but her words clog up in her mouth and she sits mouth agape, silent, waiting for the numbness to set in, wanting to maintain the machine of this fraying organism if nothing else.

Stephanie Chen

Bottle It Up

Claire Dougherty

Kids

The woman who raised me, who was not my mother, explained to my father, her son, that each should be six feet long, four feet wide, three feet deep. She wanted five planters. She wanted one for spinach, one for carrots, one for beets, two would be left available for seasonal vegetables. She handed him a diagram, instructions she found on the internet. She paused a moment after everything she told him to make sure it was sticking. When it seemed as though all of her instructions had registered, she said she’d pay him eight dollars per hour he worked.

As she turned to gather the tools he would need, he looked at me with wide blue eyes, eyes that seemed to always possess an equal amount of emptiness and electricity, and whispered, “I guess I’ll have to move nice and slow, won’t I?”

I smiled back at him. I loved when we shared jokes like this.

My grandmother told me to let him get to work. She told me she needed my help in the kitchen. She was always interrupting our fun like that, telling me I was distracting him. I couldn’t understand why she’d bring him around the house for these chores, and then keep me from him, my own father. I wanted to be near him every chance I got.

In the kitchen, my grandmother washed the dishes. She could see him through the window above the sink. She glanced up every so often, watching him between plates and stained mugs.

I offered to wipe the windows in the breakfast nook. She said I would leave streaks and she’d rather I put the silverware away, but I promised I would do a good job. I specifically wanted to wipe those windows because, like the ones above the sink, they offered a clear view of the backyard where he was working.

I watched him through the streaks I was making in the windows. He seemed to be working very hard. I didn’t understand what Grandma complained about all the time. He honestly seemed to be working very hard.

I started to feel sorry for him, working so hard as he was in the heat. It was August, or maybe July, and summers in the valley were hot and dry. Despite this fact, he was always wearing long sleeves. It made me uncomfortable just watching him. I think I might have actually been sweating for him. I decided I’d bring him a glass of water.

I waited until she left the kitchen. I filled the glass with ice, wanting it to be very cold for him. The glass was so full with water and ice, sloshing around as I hurried with it, that half of it had splashed over the brim and was dribbling down my arm by the time I got outside.

When I reached where he had been working, he was gone. I turned around and found him sitting at a chair by the pool. He was smoking a cigarette and pushing Grandma’s black pug around with his foot. The pug, though earnest in her efforts to remain balanced, was obese and pathetically easy to topple over.

I approached him and offered him the half empty glass.

“Thanks, Kid,” he said. Kid was his nickname for me.

He drank the whole thing in one gulp and I was angry at myself for not having made it outside with a full glass. He took a drag of his cigarette and pushed the pug back over. It’s funny how smell can bring you back to a particular time or memory, more so than photographs. Even now, the smell of cigarette smoke always reminds me of him. When I’m in a crowded bar, or when I pass strangers smoking outside of storefronts, I’m often brought back to this memory. The world is full of smoke from cigarettes, and so I think of him more often than I mean to.

Suddenly feeling the desire to capture his attention, to impress him even, I mentioned my new bottle cap collection.

“You know I collect bottle caps now?” I said.

“Really?”

“Yeah, I’ve been keeping them in a jar under my bed.”

It wasn’t much of a collection, just a few bottle caps I picked up from under a table at a barbecue we had attended a couple of days before. Grandma told me that they were dirty and might even be carrying a disease and to throw them away immediately. I made my way over to the garbage can, acting like I was going to chuck them, and then slid them into my pocket when she wasn’t looking. I liked the sound they made as they bounced around in my pocket. I figured they would make a good collection, and I had never had a collection of my own before.

“Good for you Kid,” he said. As he brought the cigarette to his lips, I noticed a curve of black ink poking out from beneath the edge of his sleeve.

I pointed to it. “Is that a tattoo?”

“Yes it is,” he said. “Good observation.” I beamed at this compliment. I knew he had a tattoo on his back, too. The word Daemon was spread wide between his shoulders. He had said he was young and stupid when he got that tattoo. Grandma had laughed at this, and said he still is young and stupid.

“Is it new?” I asked.

“Sort of.”

“Can I see it?”

He said he had gotten it as a birthday present for me, and that he was waiting until my birthday to show it, but if I really wanted to see it. I said I really wanted to see it. He lifted his sleeve. Elizabeth, my middle name, twisted in thick, dark letters up his forearm. It wasn’t my first name, but it was a name of mine, and it was permanently written on his forearm. He said it would last forever. I smiled so big my cheeks hurt, but I didn’t care.

When I was a teenager and still clinging to the idea of him, my grandmother told me that his girlfriend at that time, or the girl he had been seeing, was also named Elizabeth. I told her that seemed like a rational and economical decision on his part, maybe he was just trying to kill two birds with one stone. She said if he really wanted to get a tattoo for me, it should have been my first name. I yelled at her, told her she didn’t know anything about tattoos, and cried, because I knew she was right.

Beneath the tattoo, I noticed he had a scab. I then noticed that he had scabs like that all up his arm.

“What happened?” I asked, poking one. “Do you need a band-aid?”

He quickly pulled the sleeve back down over his arm. “No I’m good,” he said.

“Well what happened?”

“Mosquito bites.”

“Those look a lot worse than mosquito bites.”

“They were itchy. I scratched them.”

“I had a mosquito bite once and I itched it and it didn’t look like that. Was it a really big mosquito?”

“Hey, Kid. You ask a lot of questions.” He threw the cigarette butt to the ground and squashed it with the heel of his sneaker.

“I have a question for you,” he said. He leaned forward with his elbows on his knees and looked at me with his empty electric eyes. “Crickets. Are they real? Or do they just put speakers in residential areas to make it sound more pleasant?”

You’d think this was the most hilarious thing I had heard all my life the way it made me laugh. He was the only person who could make me laugh that way. He smiled, and in the corner of his smile, there was a tooth missing.

“What happened to your tooth?”

“What kind of a question is that? The tooth fairy took it.”

“But how did you lose it?”

“She pulled it.”

“She doesn’t pull teeth,” I laughed. “She gives you money when they fall out.”

“Hmm,” he said. “I think we must have different tooth fairies.”

“I don’t believe you.”

“Why not?”

“Grown ups don’t lose teeth!”

“Who says I’m a grown up?”

“Well, you’re my—”

“Hey. Where’s that bottle cap collection you’ve got?”

I told him they were in a jar under my bed, and if he’d follow me upstairs, I’d show him. We got all the way to the bottom of the staircase before Grandma stopped us.

“What do you think you’re doing,” she said.

“I’m just showing him my—”

“You know you’re not allowed up there.” She was talking to my father. She had this rule where he wasn’t allowed to go upstairs unsupervised. Once, when she was paying him to fix the shower faucet upstairs, she stood with him in the bathroom the entire time he worked. She also locked the door to her bedroom. The shower faucet never got fixed. He said he couldn’t work if she didn’t trust him, and he left.

“Come on,” he said. “She just wants to show me her collection.”

“I’m not paying you unless you get back to work.” They had the same blue eyes, only hers lacked the electricity. His presence seemed to drain hers of all their energy, leaving them weary and always on the verge of tears.

He stood there, at the bottom of the stairs, for what seemed like a long time, staring at her coldly. He was actually emitting a sensation that I can only describe as cold. Now, recalling this image of him, he did in fact seem quite like a statue. The same hard, sculpted features. The same pale, gray skin, like marble.

Finally, he pushed past her, walked through the kitchen and into the backyard.

About thirty minutes passed before I realized he hadn’t had anything to eat all day. I imagined him, slaving away in the heat under his long black sleeves, starving. Again, I waited until my grandmother left the kitchen before I brought a granola bar out to him.

Again, he was not building the planters, but playing with the pug by the pool.

I say playing, but really what I mean is he was dropping the pug into the pool, letting her flail helplessly for a few seconds, and then saving her, only to repeat the process. Her obesity, coupled with her old age and asthma, made this a really pitiful site. It was hard for me to watch this. I walked over to him, hoping to divert his attention away from her.

“Are you hungry?” I asked. “I brought you a granola bar.”

He left the pug wheezing on the edge of the pool and turned toward me.

“Thanks, Kid, but I’m not hungry.”

“But you haven’t eaten all day.”

“Are you sure?”

“No, I guess, but I haven’t seen you—”

“Hey! How about we play a game,” he said. “You like games, don’t you? What’s your favorite game?”

I thought about it. “I like hide and seek.”

“Fantastic. You hide, I’ll seek.”

“I thought you’re supposed to be working.”

“Can’t I take a break? We have time for a round of hide and seek.”

I smiled. He had a way of drifting about that made every visit exciting. He had a way of never stopping, so that nothing was ever dull. Grandma described it as trying to catch a fly by its wings, or a bullet between your thumb and forefinger, only to have that bullet slip and be caught in your chest. Once, she said he was like a collision between four cars and a fucking semi on a slippery highway, but that’s when she thought I wasn’t listening.

I didn’t believe her then. Then, I believed that the cupboard holding the cleaning supplies in the laundry room was the absolute best hiding spot, so while he counted, that’s where I went.

It was dark in the cupboard and smelled strongly of bleach and laundry detergent. I had shoved aside a mop to make room, but there was a broom stick digging into my back. I stood like that, barely breathing, for about fifteen minutes. It felt more like an hour, but realistically it was probably fifteen minutes. When I couldn’t stand it anymore, I slipped out of the cupboard and went looking for him.

I heard it before I saw it, another one of their arguments. She was yelling at him, telling him he was only getting thinner. He was yelling back, telling her he couldn’t eat unless he got paid.

“I told you I’m not paying you until the planters are built,” she said.

“I need the money now.”

“Yeah, I know why you need it.”

“I need it for gas.”

“You don’t have a car.”

Feeling that he’d disappear again, I ran upstairs to grab the jar from under my bed. As I came back downstairs, he was slamming the door shut behind him. My grandmother sat at the kitchen table and buried her head in her arms.

For a while I prayed for a faucet to break, for a pipe to leak, for the refrigerator to stop running. I thought about snipping one of the wires that ran out of the back of the computer or TV. Grandma had another man come in and build the planters and I prayed for an earthquake, or a meteor, to come and knock them down.

I wanted everything to be knocked down. I thought that if the whole house crumbled I could help him rebuild it.

Emily Browne

The Artist Is Present

We were performance artists

Making our drip music,

An orchestra of liquid language,

Pulling masterpieces free from our minds.

We cut our clothes in a punk prayer

Because public protests felt ours.

We braided our hair together

To weave our stories at length

And when we were tired, we slept.

But only for four and a half minutes at a time

In a straight jacket embrace

That soothed our unrelenting hearts.

We yelled and screamed and hit

Displaying the sounds of human connection.

And when we walked the

Great Wall of China to find the answers

We drew a blank by the end.

Contributors:

Emily Browne is a Creative Writing and Narrative Studies double major with a minor in Art History from Newport Beach, California. She is hoping to graduate in Spring 2016 and then travel around the world, writing about her experiences!

Stephanie Chen is a Philosophy, Politics and Law major with a minor in Communication Design. She enjoys running and sleeping in her spare time (when that exists…). She plans to attend law school following her graduation in 2015, but continue to explore art and design.

Patrick Cleland is a Junior at USC studying Creative Writing with a minor in Jazz Studies. He is the Assistant Editor of Western Folklore and his writing attempts to explore the rhythm and musicality of words. He hopes to further pursue his interests in both literature and music upon graduation.

Claire Dougherty is a junior studying Creative Writing and Communication Design. She’s from Stockton, CA.

Jean Frazier is a junior English major with Philosophy and Business minors currently attending the University of Southern California. She’s only allowed 2-3 sentences for this bio and she feels pressured to make the most of this space, so she’ll stick to the important stuff. Her interests include reading, hiking, being obnoxious during sporting events, and Froot Loops; her only dream is to keep writing (although she wouldn’t be opposed to marrying rich).

Esmeralda Jimenez: Born in a mining town in Mexico, the Washington bred hybrid now lives in LA. She studies environmental science and international relations but has a minor in coffee making granted by Ground Zero Performance Cafe and an honorary degree in sarcasm. She can also lick her elbow.

Cliff Weber lives with his fiancee, Erin, in Los Feliz. They make a really cute couple.

The work represented here is the intellectual property of each individual author and is not subject to replication or use without permission.

© Emily Browne © Stephanie Chen 2014. © Patrick Cleland © Claire Dougherty. © Jean Frazier © Esmeralda Jimenez © Cliff Weber 2014.