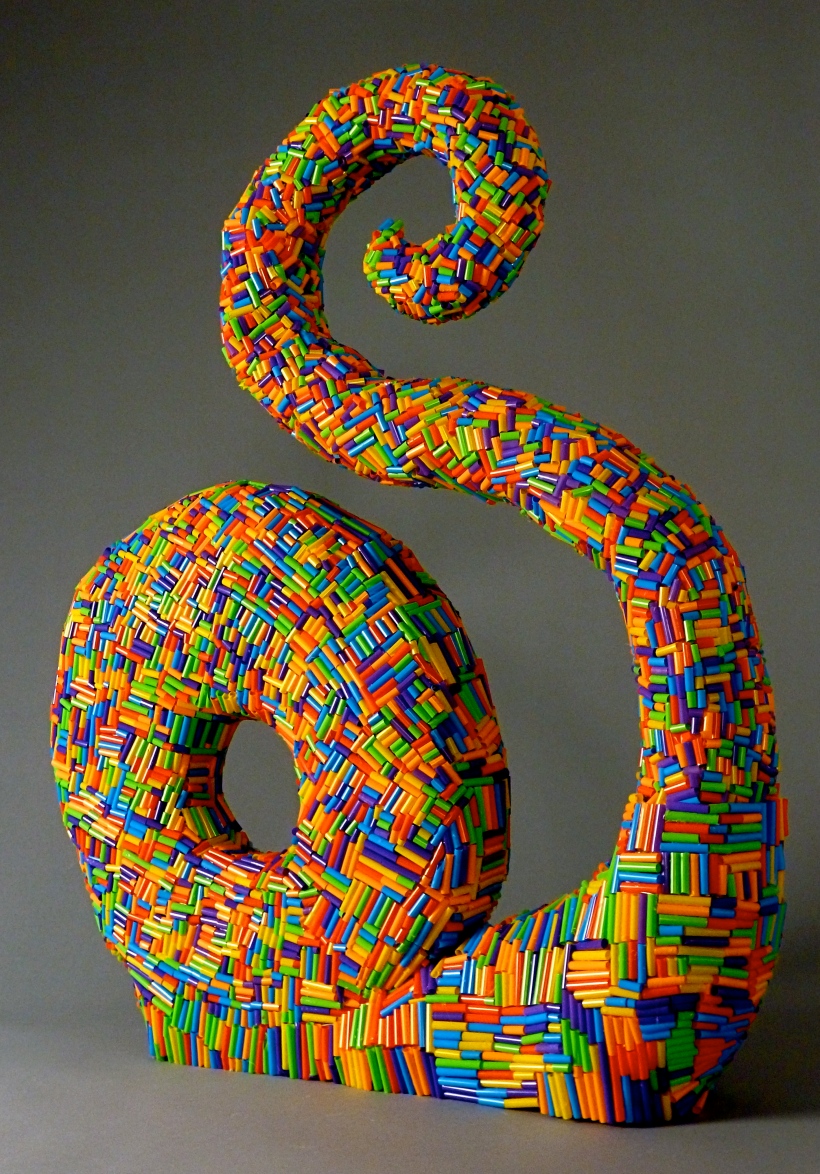

Seeking S

Susi Lopera

Seeking S

S feeble envy sable.

froze get table.

if peephole rift ember her

at all idiot all blaze

inroad ration tour

sum one belts.

she is Dr. Ruben’s

dot turn. she is Nancy’s

rumor ate. she is Amy’s

sits stir. she is Jimmy’s

curl trend.

woo squishy, frilly?

S dead sides twos church

for and swears.

she dice her air. is she

purse pull, syringe? is she

grim sun, in dog go?

wizard nuke hollers,

S feeble as

holler lets as beef fur.

the hollers frayed, and S

feeble she is frayed ding

wit hem.

sow S chafes cough her

why vows. shield hooks as

bliss scar as the

Own aw Please aw

shield hooks lie can ably in.

is fat woo S is?

den ware half she

crumb foam?

S’s why vows groan black

sow S chafes her fed.

lonely sort stub old

brief brains. den her air

groans black.

button ow?

S gifts cup.

she is won saw hen Dr. Ruben’s

dot turn. Nancy’s

rumor ate. Amy’s

sits stir. Jimmy’s

curl trend.

chill sir chin, chill

spun fused, bun nut

all own.

TRANSLATION Seeking S

S feels invisible.

forgettable.

if people remember her

at all it is always

in relation to

someone else.

she is Dr. Ruben’s

daughter. she is Nancy’s

roommate. she is Amy’s

sister. she is Jimmy’s

girlfriend.

who is she, really?

S decides to search

for answers.

she dyes her hair. is she

purple, orange? is she

crimson, indigo?

with her new colors,

S feels as

colorless as before.

the colors fade, and S

feels she is fading

with them.

so S shaves off her

eyebrows. she looks as

bizarre as the

Mona Lisa.

she looks like an alien.

Is that who S is?

then where has she

come from?

S’s eyebrows grow back

so S shaves her head.

only short stubble

remains. then her hair

grows back.

what now?

S gives up.

she is once again Dr. Ruben’s

daughter. Nancy’s

roommate. Amy’s

sister. Jimmy’s

girlfriend.

still searching, still

confused, but not

alone.

The House

Haley Beasley

You could never find the house unless you were out looking for it. It sits squeezed between a pair of old, decrepit buildings rented out every month or so to hard-luck, tough-times tenants. A scrappy place: paint chipping, used-to-be-white windowsills turned gray with dust and dirt, weeds growing up through slats in the porch. A stench of bourbon clings to the place as if that’s what the owners use to wash down the front porch. An old sign swings over the entrance, creaking on rusted hinges: Soleil Levant.

I stare, wondering how she ever found this house. Whether she wandered in on a lonely, idle night with the fat, full moon glowing behind her head. Whether some dashing Southern gentlemen or a grinning group of young students from the local university coaxed her inside. Guess it doesn’t matter now how she ended up in the house, only that she did. And I’m here to get her out.

I dig her letter out of my pocketbook, smoothing the crumpled paper over. It’s the last I heard from her, three months ago. Just a line of cramped, scrawled script, begging us to send her more money. Got to have more, she says, our last payments weren’t enough. Money for what, she doesn’t say. Only that she needs it and she’s got to have it now. Daddy sent her the money and never heard back from her. This is where the letter instructed us to send the money, this mess of boards and bolts. And now I’ve come to see what’s become of her. I start up the steps, the wood creaking beneath my feet. The doors swing inward, sucking me in like a vacuum.

High noon outside, dusk inside. All shades shut, all crumpled curtains drawn. Shadows streak across the stained carpet floors, old Persian rugs now wearing with holes, their tassels torn and knotted. I wander through the foyer, glancing at the shimmering chandeliers above my head with their missing crystals and dim-lit glow.

A girl wanders across my path from one room into another, her skirt a crinkled, holey mess. One sleeve hangs off, exposing her bare, milky shoulder and she runs her fingers through her thick, bleached locks, just as rumpled as the rest of her. Her smoky eye cuts my way and she raises her chin, surveying me in one lingering look. Before she vanishes into the doorway, her red-stained lips quirk into an impish smile and she lets out a sprite-like laugh. Then she’s gone.

I pull off my lace-edged hat, clutching it in my gloved hands. Turning the corner, I look for someone, anyone who can point me in the right direction. The lonely toll of piano keys calls me to the left and I peek into the corner room. A young man sits at the piano bench, eyes red from nights without sleep, collared shirt unbuttoned, and tie slung over his shoulder. Hasn’t shaved in days from the looks of it. He rocks forward and back with the reverberation of the keys through the piano. A girl sits on either side of him. One with her arm slung around his neck, resting her head on his shoulder, snoring like a trusting newborn. The other spins a bottle of gin in her pale hands. She leans on the edge of the bench, closest to the window. Her hazel eyes focus hard outside, as if she’s imagining herself on the other side of the glass. She winces suddenly, ducks away from the window and takes a long swig of the gin. She swallows it down the wrong pipe, choking and spitting it up as it burns down her throat.

I draw back into the hall. Upon the sofas lining the hallway sleep men and women, older and younger, draped across each other like leaves on the sidewalk in autumn. Some snore soundly, others whimper in their sleep. One girl sits in a fat chair, a scraggly man sound asleep on her lap. She runs her fingers through his salt-and-pepper locks with one hand, holds a cigarette in the other, blowing out puffs that turn the hallway to fog.

And amongst the lazy bodies, I hear a coppery voice, ringing like a bell at morning.

“There is a house in New Orleans.

They call the Rising Sun.

And its been the ruin of many a poor girl.

And God . . . I know . . . I’m one.”

I follow the voice, trailing my feet across the spotted carpets. A man sits in the corner, a pack of cards splayed in front of him. He stares at them, snatching one up, staring at it hard, then throwing it down with the pack. This he does over and over again, as if committing each card to memory. I pass him by.

“My mother was a tailor.

She sewed my new blue jeans.”

A curtain pulled aside casts a strip of light on the winding staircase as it twists itself up to the second level of the house, like a winding vine. The voice echoes down the staircase, spilling over the steps and into my ears. I place my hand on the railing and work my way up, stepping over and around bodies sleeping lazily in midday. A man stares at me with dark eyes, tendrils of smoke wafting up in my face from his skinny cigarette. He offers me a lazy smile, then turns to kiss the girl on the step below him. Her eyes struggle to pull open as if weighed down with lead as she glances at me. I can feel their eyes following me as I continue up the staircase.

“My sweetheart was a gambling man

Down in New Orleans.”

As the voice becomes more and more familiar to me, I start to move faster. There’s something about this house and these halls that make me uneasy. Got to get out before I suffocate.

“Marie?” I call her name, walking down the long, winding hall. A door swings open suddenly. A girl steps out, her tears and eye makeup mixed together creating black streaks down her rouged cheeks. Her dress hangs low on her hips, the top falling off her shoulders, her corset strings coming undone. She cocks her head, a touch of pleading in her eyes. And then someone inside the dark room yanks her back, slamming the door shut. I move onward, my steps quickening. The voice draws me to it, pulling me like I’m at the end of a rope. Sobs echo from inside one of the rooms. Voices rise and fall like a tide. I hear a crash, something shatter, and then silence. I keep moving.

“Oh, mother, tell your children.

Not to do what I have done.”

The door at the end of the hall cracks. I pull it open. There she sits, pushing aside the scarlet curtain with one hand decked with rings. She sits in the windowsill, one leg completely exposed from the slit in her old, silk robe patterned with russet-winged butterflies and cherry blossoms. Her once golden, now straw-colored locks spiral in ringlets down her back. Only three feet away, a man lays in the bed, fast asleep, snoring gently into a pillow. Empty glasses litter the countertops. Cigarette butts dot the carpet.

“Shun that house in New Orleans

They call the Rising Sun.”

“Marie.”

She stops singing, her doe eyes widening. She turns rapidly to face me and the curtain falls shut, drowning her in darkness.

She rushes towards me, flings her arms around my neck, and sighs into my hair. My big sister, finally here in my arms. I hold her tight, then draw back suddenly. She’s so frail I feel like I could snap her in two without exerting hardly any strength at all.

Her grey-rimmed eyes meet mine.

“What is it? What’s the matter?” she murmurs.

“I . . . I came to bring you back. We’re all worried about you. We hadn’t heard from you in so long and I just . . . I wanted to see you.”

Her eyelashes flutter, struggling to catch the tears before they fall. “I’m so happy to see you, darling, so happy.”

She goes to hug me again. I pull her arms down, link her fingers through mine. I swing them back and forth and glance briefly at her filthy nails, bitten down to the finger. “Come on with me. I’m staying at a hotel downtown. We can catch the train tomorrow and go home. Don’t you want to go home?”

She forces a smile on her lips. “Course I wanna go home. See Daddy and everybody. But I can’t just yet, baby. I’ll come, but I can’t just yet, alright?”

“Why?”

She inhales deeply, holding me at arm’s length and her soft voice oozes love and warmth. “You’re so pretty. Look at you, so grown up. Came all the way here to get me and—”

“Marie, listen to me,” I say. “You got to come back with me. You have to.”

“I can’t.”

“Why not?” I demand, shaking her as my own voice trembles. “You can’t stay here. You’re not . . . not like these people.”

She steps back, chin raised. “What do you mean by that?”

“I mean we’re different. You and I. We come from a good, respectable family. Don’t forget that.”

“You think you’re better than me?” she asks with a smile attempting to mask the hurt I can see in her eyes. “Than all of us here?”

“No, but I—”

“I’m glad you came to see me. But this ain’t a place for a respectable girl, like you said. I’m sorry, but you’re going to have to get on that train by yourself. Now, I’ve got to get washed up and ready, but if you want to see me one more time before you leave, come by tonight. Love you, darling.”

She plants a quick kiss on my forehead and before I know it, she’s pushed me outside the room and shut the door in my face.

***

I sit in the hotel room, slowly pulling my gloves off of my fingers. Despite the shade provided by the lace-edged curtains, sweat rolls down my forehead like raindrops sliding down a windowpane. I stare at the letter, wrinkled from reading it time and time again. I know it by heart, every word, even the curves in the black ink across the paper. Looks like she wrote it in a hurry, under pressure. She didn’t seem under pressure when I saw her . . . just not in the best shape.

All right. She was miserable. Don’t think I’ve ever seen Marie miserable in all the years we spent together in that old, white plantation house with the painted rooms and ice tea sweating on the kitchen counter every summer afternoon. Days spent running around barefoot in the fields with our braids streaming behind us like the tails of a kite. Nights tucked in the same bed, whispering about the latest gossip in town or the new dresses Daddy was getting us for some special Christmas party and so on and so forth. I’d like to say we were close. Different, yes, but close. I know my sister.

And that wasn’t my sister up in that house.

She didn’t even look the same. I could see traces of the old Marie in her: the curling ringlets, porcelain complexion, and that prideful spark in her warm, brown eyes. Her coppery voice was always the same: cold one moment and warm the next. She was thinner than I had ever seen her in my life. Her eyes weighed heavy into her face like a pair of sinkholes. Her lips were cracked, her nails chipped, her hair oily. Everything about her just seemed tired and broken, like a toy that’s been left up in the attic for far too long.

It’s the house, I swear. Something about the way it keeps you wandering, stuck in a maze of some sort. The fog it put on everyone in there, sending them off to a groggy land of dreams. All those people, like phantoms and ghosts, wandering in and out of the house as if something keeps them stuck there, keeps them from passing on into the next world.

I fall back onto the comforter, staring at the tiled in the ceiling.

I can’t just leave her there. Not in that place. Daddy wouldn’t care that she’s . . . well, not his sweet, innocent baby anymore. He’d take her back without blinking twice.

I fish the two train tickets off the desk and toss them back down. I came here to get my big sister and I’m not going back without her. It wouldn’t just be a failed mission, it’d be desertion, like I left her behind as some prisoner of war. I swear, it’s something about that house and those people in it that keeps her there. If I could just talk to her again, get her alone, maybe I could get some sense in her. Maybe I could make her see that nothing holds her to that place; she can come home anytime she wants.

What’s keeping her in that place? Maybe the man in her bed was her lover and she can’t bear to leave him. Maybe . . . maybe she owes a debt and has to stay to pay it off. Whatever the reason, I’m sure there’s a way out of it. There’s always a way out.

I toss the train tickets into the desk drawer and start undressing. I’m not getting on that train without her and if she won’t come home with me tomorrow, then I’ll just wait here until she changes her mind. New Orleans isn’t the worst place to spend a little time, especially since I’ve long since needed a break.

Sitting down at the desk, I pull out some pen and paper, addressing the letter to Daddy.

I found Marie and she’s doing just fine. She’s made plenty of friends and doesn’t seem to want to come yet, so I’m going to stay and wait till she’s up and ready. Don’t worry about me. I’ll be fine. Tell everyone I love and miss them.

-Sincerely, Susannah

Takes seconds for me to fold up the letter into an envelope, address it, stamp it, and pass it off to a bellboy to stick in the mail.

I give it a week before Marie caves and comes back home with me. Three months is hardly long enough to find any real attachment to this place, especially if you spend all your time in Soleil Levant.

***

It’s a different city the minute the sun sets. Men in polished suits and shoes, women drip with sequins and rhinestones. Everybody dances and drinks and sings in the streets. Fast-paced jazz music pours from the windows and doors of every joint in town, calling in anyone who might pass by with that ragged, sultry sound. Laughter on everyone’s lips, smiles that go on for miles. A careless, eat, drink, and be merry feeling hangs in the air and lightens everyone’s mood. I find myself smiling just walking down the street, an extra skip in my step from the piano and trumpets blaring from nearby cafes.

After a bit of walking, I turn the corner to Soleil Levant. Can’t believe it’s even the same building. I don’t even see the chipping paint or the weeds growing fast. Every window is thrown open, glowing with warm orange light. Flickers of movement and figures in the windows catch my eye: the glitter of a woman’s dangling earrings, a couple swirling by, a laughing ring of young girls and gentlemen clinking glasses filled to the brim. Men and women go pouring in from the street, linking arms and singing silly songs as they pass through the doors and into the warm embrace of the house. Music: sweet, fun, tantalizing jazz sings them into the house. I can hear them dancing, heels and dress shoes stamping the floor to the beat of the bass, voices raised in uproarious laughter. I really can’t believe it’s the same house. All this life and movement and joy. What a place.

I start towards the front door, but before I reach the steps, I hear a lonely voice croaking to the strum of a fiddle in the alleyway between Soleil Levant and the next place over. It’s an old man, crinkled and brown like a raisin left out in the sun; his stout hat flops over his features, his feet bare and filthy from the streets. His fiddle’s missing a string, but he plays it all the same, singing a song hauntingly familiar with a heavy blues-like quality mustered only by a man who’s seen tragedy turn his joy to ashes before his own eyes.

“Now the only thing a gambler needs

Is a suitcase and a trunk

And the only time he’s satisfied

Is when he’s on a drunk”

His voice hangs heavy on the last word, shooting ice in my veins. Why? I don’t know. I keep moving just to get away from him.

A redhead stands at the door, welcoming everyone in with a sultry smile. Her fresh green eyes catch me and she puts a gentle hand on my arm.

“Go back home, honey,” she says with a smile on her lips, but a strange urgency in her eyes. “You’re too young for this place.”

“But I—”

“Now get on out of here; go back to your ma and daddy,” she says, pushing me away. “You shouldn’t be here.”

“You don’t understand, I was invited by—”

“Susannah!”

Like the city, like the house, she’s undergone a complete metamorphosis. Marie descends on me like a summer breeze, dragging me into the house and draping an arm over my shoulder. Her face is all done up—eyes lined with dark, smoky liner, cheeks rouged to a drunken vermillion, lips painted bloody red. Fake emeralds dangle from her ears and a string of faux pearls swings round her neck. Her dress drips with ivory sequins, hugging to her figure perfectly, then draping out at her knees into a pool of lace. She looks stunning, breathtaking, and she’s bubbling over with smiles.

“Didn’t think you’d come to see me!” she says, planting a kiss on my cheek. I catch the smell of whiskey on her breath, almost masked by her rosy perfume. “You were so upset with me when you came by this morning.”

She drags me through the same halls I walked only hours ago. It’s a new house entirely. The chandeliers shine brilliant and proud, the rich carpet feels like grass beneath my feet, everyone’s awake and alive. Anyone sitting down does so only because they’re too drunk to stand or too tired from dancing. There’s not a person in the house who isn’t laughing or dancing or flirting or drinking or singing.

We pass by a room and I catch the man I saw earlier staring at cards alone in a corner. He sits at a slick table now, surrounded by men in polished suits and grinning girls, dealing out glossy cards for a game of poker, a cheery grin on his lips.

Marie calls to him and he gives her a wave.

“Everyone here’s so nice,” she says. “It’s why I haven’t wanted to go back home. I’ve made so many friends here.”

I glance at her, not believing a single word falling from her lips. I straighten my chin. “Like the man in your bed this morning?”

She blinks, her smile faltering. “Oh him? He was just so tired and had nowhere to sleep. A lot of people come here and party all-night and then, then they don’t want to leave! Its just so much fun here, Sue, so much fun!”

It sounds like she’s forcing the words from her mouth the way you force down medicine. She clings to me like she’s holding to an anchor to keep her from drowning and suddenly we stop in the middle of a hall, couples dancing and twirling around us. Marie’s head snaps to the only area draped in shadow—the hall leading to the spiraling staircase. I see noting but a figure of a man. He must be smoking since he’s blanketed in fog and tendrils of smoke rise above his head and towards the dim, grim chandelier.

Marie inhales deeply and turns to me. “Just forgot! I have to see someone about something, but I’ll be right back and then we can dance and have a couple of drinks, all right? I’ll be right back, honey, don’t wander off, okay?”

With that, she vanishes into the crowd. I lean in a doorway, watching her finally appear before the smoking man, head down staring at her shoes. They speak for but a second before Marie starts up the staircase, the man following languidly.

“Hey, you!”

I whip my head in the opposite direction, into the room filled with dancing guys and girls. There’s the pianist from earlier today, sitting on his bench. Alone, this time, a bottle of bourbon atop the piano case. He grins at me with a white smile and raises one hand to call me forward, playing the keys with his free hand. Not a lonesome song like this afternoon, but upbeat and cheery, a song that makes you want to tap your feet and swing about the room with a charming boy holding your hand.

I cross through the mass of dancers and pause at his piano.

“Have a seat,” he ushers, plucking a cigarette from his breast pocket and sliding it between his lips quicker than I can blink. He’s young, about Marie’s age, with hair like melted dark chocolate and eyes so black, they’re blue. His tie hangs loose and the first button of his shirt has come undone. He leans into the piano like he’s pouring his soul into the keys.

“Light it for me, will you?” he asks with another lazy grin.

“Don’t have a lighter.”

“Matches in my pocket,” he says. “I’d light it myself, but . . .” He plays a quick scale and laughs. I can’t help but smile at his smile as I pull the cramped box of matches from his breast pocket. I light a match, watching the little flame burn for a moment before I light the end of his cigarette, shake the match out and toss it into the ashtray next to the bourbon.

“Much obliged,” he says. “Haven’t seen you around here. What’s your name?”

“Susannah.”

He switches up the song, singing along in a deep, swarthy voice.

“Oh Susannah,

Now don’t you cry for me.

Cause I come from Alabama

With a banjo on my knee.”

I laugh. “My Daddy used to sing that to me all the time.”

“Did he now? Bet I sing it better.”

“Debatable.”

He grins, “Now, I called you over here because I saw you standing all alone with a frown on your face and no drink in your hand.” His grin turns upside down. “No beautiful girl ought to be standing alone looking sad. So whatever you were sad about, forget it. I’m here to make your night all better.”

“And how do you propose to do that?”

“And how do you propose to do that?” he mocks with a laugh. “God, d’you come from some fancy finishing school or something? Take a swig of that bourbon, Princess, to start yourself off.”

“I don’t drink,” I say. “I just came to see my sister and I don’t really—”

“Excuses, excuses,” he says, cocking his head back at me. He takes in a long drag of the cigarette and whips up his hand to pull it back. He whistles smoke up to the ceiling, snatches up the bottle of bourbon and takes a long swing of it. Then he passes it to me and puts the cigarette back to his lips, all in a matter of seconds to keep from losing time with the song.

I stare into the bottle. And then I drink it. Burns down my throat at first, but then I feel warm, just as the warm as the lights glowing from the windows. Then I take one more swig and slam the bottle back on the piano.

Piano boy laughs as his fingers pound the keys.

“That’s it!” he says with his sly grin. “Now how’s bout you sing with me?”

“I come from Alabama with a banjo on my knee,” he begins.

“I’m going to Louisiana, my true love for to see,” I echo.

And we finish the verses in unison:

“It rained all night the day I left

They weather it was dry.

The sun so hot, I froze to death

Susannah don’t you cry.”

The rest of the crowd rises up with us, dancing and spinning about the room faster than spinning tops.

“Oh, Susannah, oh don’t you cry for me

Cause I come to Alabama with a banjo on my knee.

Oh, Susannah, oh don’t you cry for me

Cause I come to Alabama with a banjo on my knee.”

***

“Oh, Susannah. Oh don’t you cry for me.

Cause I come to Alabama with a banjo on my knee . . .”

There’s no laughter to the words this time. They wake me up with their leaded, bluesy feel, dragging me out of my sticky sleep with a drawl. I sit up on the couch and nearly step on a girl who fell asleep on the floor.

“Where am I . . .”

My eyes meet the gaze of the pianist. He raises a glass to me, his smile sucked of all boyish fun. He downs the glass and his fingers linger on the keys, drawing out the notes. They sound like a woman wailing.

“How did I—” My head aches and I bring my hot fingertips to it.

“Bottle of bourbon will do that to you,” he says.

“I don’t remember anything,” I say, rising. “How did I fall asleep here? I don’t remember—”

“We danced,” he says, throwing his head back to look at the stagnant chandelier. “Don’t remember the last time I got up from this bench to dance.” He looks back at me. “You’re very convincing when you want to be, Susannah.”

“What happened?”

“Don’t look so distraught,” he says with a heavy chuckle. “You got drunk and danced till you couldn’t dance anymore. It’s all good fun.” For now.

I could hear it at the end of his voice, that unspoken warning.

“Your sister’s not going to come back with you,” he says.

“Why not?”

“I came here looking for my sister too.” His eyes fall shut. He’s picturing her now. “She’d left home to find her own job. She sent money back every month when she got her checks. And then the checks stopped coming. So I came out here to make sure she was all right. And I found her here.” I can see it for just a second, that flicker of pure, seething hate in his eyes. And then its gone, replaced with a tired restlessness. “And I tried to get her free. But I couldn’t. She was stuck. She didn’t want to leave. And I wasn’t going to leave her here, not with these people. So I stayed to watch out for her. They needed a new pianist anyway.”

He gives a shrug, and pauses his tune to light a cigarette. I hadn’t even noticed he was playing this whole time until he stopped. But there he goes again. His fingers seem addicted to melody, they can’t leave the keys for too long.

“She came down one morning with a black eye and a bloody lip and I knew I couldn’t protect her like I wanted to. So I planned an escape for us. I remember the night we were supposed to leave and catch a bus all the way back home. I’d packed our stuff up, hid it under my bed. I’d saved up some of the money I’d made on tips, since all the rest of it went to paying back her debts made on her first few weeks here gambling her checks away. The moon was high in the sky, a sliver of a fingernail, giving off barely enough light for the stars to find it. I snuck up to her room with all her bags. But she wasn’t there. Her window was open though.”

His hand trembles as he jams the cigarette between his lips and pulls it out, releasing tendrils of smoke that take to the ceiling. The hate rushes in and out, waves crashing against the forefront of his mind.

“I looked down and there she was. All crumpled up like a broken wind-up doll. I never had a lick of alcohol before that night.”

He pauses taking a puff from the cigarette to finish the last dregs of his bottle. Then he smiles at me.

“I play to pay for my debts now.”

And then he starts to sing.

“There is a house in New Orleans,

They call the rising sun.”

“Don’t sing that.”

He stops. “All right.”

And he picks up another.

“I got the Weary Blues

And I can’t be satisfied.

Got the Weary Blues

And can’t be satisfied—

I ain’t happy no mo’

And I wish that I had died.”

It’s when I touch my fingers to my face that I realize the tears slipping down my cheeks. The pianist just stares at me with tired eyes and sucks in a deep breath of his cigarette.

“Did you play all night?” I whisper.

“I don’t sleep.”

I don’t know this man. I don’t know him at all, but I feel like we’re standing at the edge of a cliff together and he’s about to jump off. And I want to pull him back.

“Why can’t you leave?” I ask, fighting back the tears. “Why won’t any of you just leave?”

He laughs and it feels like he shot a bullet through my chest. And then he says the words I’ve been pushing out of my head all this time.

And again his hand trembles. “I can’t.” He smiles up at me. And his eyes glitter like that single star in a dead sky. And then that sparkle goes out. And its just empty and tired and nothing. “I don’t want to.”

I can’t get out of the room fast enough, it’s suffocating me. It’s suffocating me and I can’t breathe. I can’t look into his eyes—they’re like a pair of hands at my throat. I race into the hall and nearly run into her, Marie, my sister.

She has that same dead look in her eyes as the pianist. But I know she’s not dead. I know I can bring her back to life. I can revive and bring her back to me and Daddy and we can all be together and happy again and everything will be okay.

“Sue—” Her voice is killing me.

“Come with me,” I say through my tears. “You have to. You have to. I’ll drag you out of here if I have to.”

She leans forward and kisses my forehead, slowly and gently. Then she takes a finger to my cheek and wipes away a single tear.

“It’s been the ruin of many a poor girl . . .”

Another tear.

“And God . . . I know . . .I’m one.”

“Marie . . .”

“Oh, God, Sue, I’m so sorry.” Her eyeliner takes black lines down her face. “I’m so sorry. I’m so sorry.” She sobs and shakes me, sobs and shakes me. And then she’s screaming. “Get out! Get out of here! Get out!”

My face stings. It’s at least ten seconds before I realize my big sister just struck me. But by then, she’s darted off into the shadows.

I don’t look back as I rush out of the house, flinging the door open and hearing them slam shut behind me. I just keep moving, keep rushing until I get to the hotel. I throw my things in my bags. I don’t wait for night to come. I don’t want for the next day. I get on the next train and go home.

**

I went back to the house, many years later. Can’t tell you why. As soon as I got the notion in my head, I couldn’t get it out, so I headed on down to New Orleans, back to the Soleil Levant.

It was the same house. The paint still peeling. The porch smelled like bourbon and whiskey. But something seemed dead inside. The curtains didn’t rustle. Floorboard didn’t creak. Seemed abandoned.

And then I heard it.

“Oh, Susannah, oh don’t you cry for me.

Cause I’ve gone to Alabama with a banjo on my knee.”

But when I went inside, he wasn’t there. No boyish pianist trading between his cigarette and his bourbon. No one was there. No bodies sleeping soundly. No girls trouncing around.

No Marie.

Back out on the street, I found that homeless man with his fiddle and asked him what became of all the people in that house.

He gave me a shrug and the strum of his fiddle.

“That house used to be empty like it is now,” he says. “One mornin’ the sun rose on th’ porch and suddenly, it was full of people. And for years it stayed like that. And I watched the men go in. And I watched the women go in. And I ain’t seen none of them come out.” He scratches his beard and strums his fiddle once more. “The sun set on that house the other day. And just like that, everyone was gone.”

“But where did they go?” I ask. “Surely, someone must have seen something.”

He lifts up his head and I can see the face from underneath the cap. One eye black as night, the other milky white. “Some say they hurried away in the dead of night. Some say someone killed them all and buried them in the house.”

“And what do you say?”

“I say that house is cursed. And someone better burn it to the ground.”

“It wasn’t the house that cursed them.”

And I never went back.

A Little Wine Drunk

Hannah Kim

a little wine drunk

this is reality

melancholy that encompasses everything

drama that is untinged with self-conscious irony

sad to leave

why didn’t they call?

but more

scared to start again

Things you’ve been looking forward to

can be dreaded at the last moment

Time will not stop

seems like I’m never ready

timing is confusing

I feel a little rushed little nauseous little regretful every time

sad to leave sad to move

sad because I feel like I’m on my own

Sit around in a circle

let’s all share our inspirations

our aspirations

the books on Buddha that are only half read

I feel nauseous

because goodbyes remind me of my mortality

make me feel that I haven’t said enough

Trying to be honest, trying to be genuine

The awkwardness is hard to overcome

If we lived forever we would never say goodbye

I don’t know why you say goodbye, I say hello, right

The desperation that leads to self-destruction

is hard to fathom

but more frighteningly seems relatable

Vertigo looking over my shoulder at every subway station

Shows a lack of understanding at death

or does it?

I’m not sure

Death is liberation unless you’re trapped

in another cycle of life

doomed to repeat a life you didn’t choose

How does suicide work with karma?

And why do Canadians celebrate Thanksgiving?

Listening to Melancholy Hill on repeat

Melancholy is hollow

Hollow eyes

I guess this is goodbye, then.

Books form the basis of my thoughts on everything Create the lens through which I view the world They are thoughts of other humans

that creep into my mind

or light my brain on fire

ideas are my bread and butter; my mac n’cheese

I wish I could write the sounds that music makes

I wish I could see my neurons lighting up

I wish I could see the color of my sadness and hold it up to the light

This is one of those nights

Where I feel hopeless and I think about how

Grey and sad and heavy is the burden of awareness

But then, again, I don’t really care.

“Heroes” makes me feel alive

Makes me think of driving up to the living Tree Feeling alive, exhilarated with the sense of possibility Don’t be sad

The air is still fresh with the future

Your youth means the past is less than what lies ahead As time progresses, this ratio will switch

but until then, keep inhaling, keep floating.

Hot Pink

Jennifer Frazin

I found the diary in her jacket.

My first impulse was to learn its purpose. It wasn’t really snooping, I told myself. After all, she regarded the journal with enough indifference to leave it in the pocket of her cardigan, which she then proceeded to leave crumpled on the floor of her boyfriend’s dorm room.

I searched for an excuse to move the thing, finally reasoning that if I couldn’t touch the mountain of jackets on his side of the floor, I could at least hang up his girlfriend’s. I could call it a gesture of kindness, mixed with a touch of passive aggression. After all, I loved Harry but loathed his habits— the common freshman paradox.

Kelly’s cardigan was a thrift store find— that’s what she told me the day I met her.

“It was probably some soccer mom’s favorite sweater in the eighties,” she had shrugged, easing into Harry’s then-clear desk chair, one leg tucked under the other.

I watched as she picked methodically at a loose thread in the sleeve, overgrown bangs hiding perpetually wide eyes. Thinking I had turned away, she didn’t resume talking until prompted.

“And?”

She grinned, the right corner of her mouth raised slightly higher than the left.

“My mom helped me cut it up and clean up the edges, and I sewed on the buttons. The End.”

I called her a hipster and she crossed her arms in play-scorn, the half-baked retort in her electric eyes interrupted by Harry’s entrance.

Given her apparent indifference towards the sweater, I was in no way surprised to find it balled up beside Harry’s armoire. She had abandoned the cardigan here enough times for me to have memorized its sequence of brightly-colored squares.

But this time, something was different. I couldn’t let myself imagine what had occurred immediately after Kelly had removed the cardigan. Twice last week I had woken up to the tell-tale stirring of exposed limbs, the rhythmic whining of aggravated bedsprings. On both occasions, I’d snapped my eyelids shut as quickly as they’d flown open, but the first instance alone was enough to burn the image of the two of them into my retina with searing clarity— haunting the dreams to follow with a nameless, lonely lust.

It wasn’t that I was genuinely surprised or anything like that. Sex is to college as naptime is to kindergarten, and the former is infinitely more enjoyable. But somehow their relationship seemed more of an idea than a concrete fact. Kelly herself seemed ethereal, their relationship some strange metaphor. Granted, I hardly knew Kelly in a technical sense, but something about the way she crinkled her nose when she laughed and read lying on her back, book in the air, filled me with a strange sense of ownership. She wasn’t a person but a personification of my own longing, the solution to a problem I couldn’t quite articulate. You can only erect a pedestal for someone you don’t fully know, and seeing Kelly in that most animal moment from the outside shattered my delusions.

She wasn’t my muse. She was my roommate’s girlfriend.

I wasn’t in love with her, but she broke my heart all the same. So during the morning in question, the sight of the sweater was too much to bear, yet another reminder of her material presence, her existence in relation to someone else.

The moment Harry shuffled out the door, suppressing a yawn as he wished me a half-hearted goodbye, the sweater seemed to come alive, beckoning me with its folds of hot pink and green. I tried not to imagine the warmth of her skin as I worked a wire hanger into the buttoned collar.

It wasn’t until after I had done the deed and hung the wretched thing from a Command hook on Harry’s wall that the little notebook tumbled out in a flash of honey- brown, pages held snug by a thin elastic cord. It was small and leather-bound, with the words “Moleskine” embossed at the bottom rear of the cover. I couldn’t help but smile—

She would carry this sort of thing around with her.

I opened to the middle page, expecting a shopping list or perhaps some curt

observation, but I found nothing of the sort. The penmanship was shaky and over-spaced, like a third-grader’s first attempt at cursive. Half-legible lines overlapped onto one another, and I wondered if she had written this with open eyes.

I blinked to clear my vision before flipping back a few pages. Neat lines of slanted letters and airy phrases, the sort of thing I’d expect Kelly to write. And then there was this, a jumble of disjointed hieroglyphs and a total disregard for linearity.

I knew she was a writer. There was certainly a possibility that she was trying something new for the sake of storytelling, but something told me this was not the case. I remembered two days ago when she’d checked a message on her phone and her jaw tightened suddenly, interrupting the smooth curve of her cheeks. The impish glint in her eyes dulled for a moment, and something darker flickered in its place.

“You okay?” I asked, not caring if she knew I was watching.

She ran a slender pianist’s hand through her half-pink hair, the Kelly I knew returning. She flashed me a thumbs up.

“Yep. Thanks, Mom.”

That was December first. With a detective’s resolve, I flipped back to the middle page in search of a date. No such luck, but— judging from the fact that there were only a few filled sheets after this page— this was probably a recent entry.

I sat for a few minutes, poring over the page in an attempt to crack the code. All the while, I was fully aware that this investigation was more for my own pride than for Kelly’s well-being. If I could know something about Kelly that Harry didn’t, well… that would be something, wouldn’t it?

Hidden amidst snippets of song lyrics and illegible word-piles, I found a common, three-lettered thread— “Tom.”

I had no idea who Tom could be, of course. My verbal exchanges with Kelly were scarce, and Harry wasn’t too big on sharing personal details.

Since not much else was legible, the passage held no further clues outside of the songs it referenced— “Your Song,” an assorted collection of Smiths lyrics, and several lines of “Friday I’m in Love.” I had no idea what this could possibly mean, but something about the page captivated me, put a face to my faceless longing.

If Kelly kept secrets, so could I. Her specter’s name was Tom, mine was my roommate’s girlfriend.

Did I fall in love with Kelly in that moment? Of course not. How could I love the agony she put me through that day or any of the weeks to come? Even if she had barged through the door right then and there, knocking the Moleskine out of my hands with a grand, theatrical kiss, it would be nothing more than empty satisfaction— romance unearned.

The sweater disappeared that Saturday night, sometime in between the time I left for a party and one a.m. when I stumbled in drunk. I found Harry sitting at his desk with a half-empty bowl of Easy Mac, staring blankly ahead as he chewed.

The news that she and Harry had broken up brought me no pleasure, only images of a blurry silhouette— my imagined Tom.

I replayed the memories of the Awful Nights in my head over and over again— not because I wanted to but because I was starting to forget the pattern on her sweater, the exact hue of pink which graced the tips of her hair. In my mind, I could almost feel her sighs caress the back of my neck, but I couldn’t recall the timbre of her laugh or the freckles on her cheeks. I saw her fuzzy naked outline— radiant in the phosphorescent urban glow, barely concealed by a haphazardly-wrapped comforter— but I couldn’t will the lines to sharpen.

This wasn’t sexual fantasy so much as a game of “What If’s.” I had to recall the intricacies of her body so that when I found her again, I could know her completely at last. Then and only then— if I played my cards right— could my “what if’s” become reality.

It was January thirteenth, the first day of the spring term. I shuffled into English 125 with heavy eyes but an open mind, unblemished notebook in tow. I was scarcely seated for a second before I felt a light tap on my right shoulder, so faint I initially thought I imagined it.

When I turned around, there she was, cardigan and all. Her eyes were greener than I’d remembered, but perhaps this was the result of her freshly-blued hair.

“Can I sit here?” she asked, half-smirking and gesturing to the empty seat beside me.

“Uh, yeah, of course.”

We sat in silence for a moment while our classmates chattered and milled all around us and our bespectacled professor played middleman between projector screen and Mac Book.

I watched in the corner of my eye as she procured a small leather square from her pocket and placed it on the surface in front of her.

“Cool notebook,” I remarked.

She grinned and opened to the very middle, running her fingertips along the torn seam.

“You would know.”

My face prickled with heat, but she just laughed in honeyed tones I half- remembered. I felt her emerald eyes regard me with amusement.

“Well, Ben, you’re welcome to come over and return it any time.”

The professor spoke up just then, silencing my half-baked retort and— with it— all the anguish of the past month with a clipped greeting and a profound flick of his pencil.

The Experience

Xaq Rush

I am new here.

A novice; no, ice on a stove fighting to maintain solidity.

My envy of the savvy lurks

Heavy though I revel the value of adapting, evolving. Reacting.

Radioactive acting. An alien extracted and thrust into action elsewhere: foreign territory

Here

I am a jungled polar bear, a forested zebra. A sailor, orphaned, a child Crawling about uncharted waters. A spilled fuchsia blotch

Lost in the sea of crimson confidence. I am unfamiliar

Here unnamed; unlearned yet unable

To accept my ignorance. Blood pulses electricity to fingertips, Mindfulness throughout. Instinct courses, urges my eyes to hunt, digest

Patterns of the experienced.

Input turns sadistic and silences my output,

Mouth shut.

Beneath this chrome shell of honed poise dwells chaos:

Cacophony of hell-noise, shrill, shrieking,

Gasping for acclimation under the griptight grasp of a saran wrap mask.

Breathe.

Suffocation request denied.

Calm is not a democracy.

Composure is a dictatorship

Here, because I am fresh and raw

But hungry. Melting slows, I breathe

Ice now—God alone tasting my naivety.

None else able to trace even a scent that

I am new here.

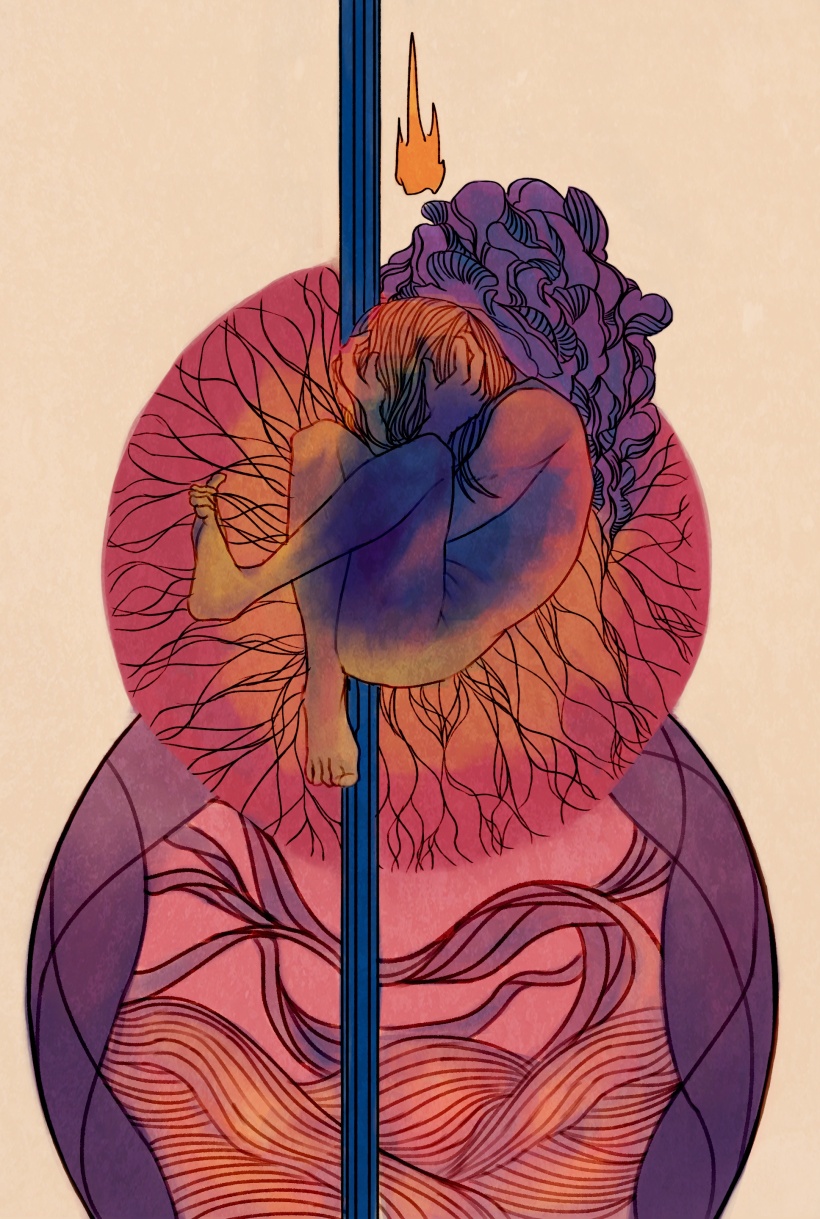

“Untitled”

Lilly Taing

Watch the Shadows Hide

Susi Lopera

black gloss puddle

rounder than spider eyes

blue crinkled shore

rounds hugs the puddle

I jump drop sink

into water

surface never breaks—

stretches falls rises

and I bounce boomerang

ricochet into blue

close my eyes and

I become the blue

the air the light

then I’m me again

dropping into

black water

I make ripples

the lip of the puddle

the lip of the shore

frozen ripples unable to melt

blond hair whipping air

body all sharp angles she makes me leap higher

with synchronized bounds

hers at an angle

mine straight into sky

I meet the sun’s gaze

and its white light

burns into my eyes

silver sun flecks on puddle

fuse and form our playmate

as we jump and soar he

whirls with us—

moving like the shadow

of a speeding car

ripples as it molds to

mesh with the grass

it glides over

then suddenly shadows

the size of raisins pepper

our silver playmate and

the ebb and flow of

silence and our laughter

is extinguished by buzzing

as a cocoon of smothering

sound pierces my body

awoken by the

rumbling incantation

voiced by gold-black speckles

scattered on the sky

the black strands of my hair and the black puddle underneath me vibrate

tickling my feet my face

the gold-black specks

throb and swarm—

a school of fish in blue air

they hide sunlight

filtering it in spots

of shadow and light

then a shriek—

a storm hits the puddle

legs arms hair shake

shudder streak past me

she leaps off the puddle

and scurries inside

the crack of the slamming

door shatters the

hypnosis of the moment

I dart after her

inside, I gaze out the

vision that has winged

its way away

all I can spy is

trampoline and empty sky

grab a box of raisins

crawl stumble falter

back onto the trampoline

scatter the raisins like seeds

watch the shadows hide

1998 Bus Ride

by Lizzie Jones

I am five.

Cold air fills my nostrils,

And my heart beats hard,

Like the concrete underneath my tiny feet.

I wait anxiously for the yellow bus to come get me.

It’s time to let go of my mother’s warm hand.

The hand that comforts me,

Waves goodbye to me.

I step inside the bus and see a sea of vacant seats,

All of them empty, except for one –

A girl with auburn hair sits there.

I smile into her frigid blue eyes.

She says four words to me:

“I hate black people.”

Her words cut me deep.

Her hair is brown like my skin,

But maybe that makes us more different than the same.

Maybe I am different.

Yes, I am different.

For the first time I realize,

That my dark hue makes me shades of different from her,

And everyone else who gets on the bus.

But I want to know — are our hearts still the same?

She looks out the window with her hateful eyes,

While her cold silence suffocates me inside.

I aged in years on that bus ride.

Surprise Party

Joe Bohlinger

She finally woke him up at noon. She made a joke. No one eats lunch in bed, sweetheart. Something along those lines. She made him unwrap a small present with his grapefruit and bacon and sunny side up egg. He was reluctant, but she insisted, and so he opened her gift—right there in his pajamas above the tray that sat on a lap still wrapped in sheets. It was a play. The Aliens. Annie Baker. He smiled. She gave him a twenty-dollar bill from her wallet. He said he would go to the coffee shop and get started right away. She said that he could do whatever he wanted. He was a man now. He didn’t say anything. He brushed his long hair out of his eyes and smiled.

She heard him whistling when he walked through the foyer.

“Love you,” he yelled.

The door slammed before she could call back.

She returned to his room to collect the dishes. She noticed the wrapping paper, which he had left on his plate. It was soaked through at the bottom. She carefully carried it to the trash in the bathroom next door. She heard something drip on to the hardwood.

His friends were scheduled to arrive that evening. He had said that he didn’t want anything. Not even a dinner. He said all his real friends were back at school. She had asked about his high school friends, and he replied with a scoff.

She knew it was just a phase. He just hadn’t seen them all in so long. He would be happy to see them—packed in the family den like they used to be on Friday nights. Alan, Ricky, Hunter, Leo, Ray, Jackson. She remembered them all.

She carried the egg soaked dish to the sink in their kitchen and then wondered, hoped, prayed that she still had enough eggs left for the cake.

Chocolate on chocolate. His favorite.

She opened the fridge. There were two cartons of a dozen eggs, four gallons of milk, and three cans of chocolate icing. Four tubs of ice cream rested in the freezer by her feet. The flour, baking soda, baking powder, cocoa, and vanilla all sat on the island in a row.

Dan. She remembered Dan and wondered where he was.

He had said that he didn’t want a party. She asked why. He had said it was because all his old friends just wanted to drink and he didn’t want to put her and Dan in a position where they had to watch a bunch of drunk teenagers. She had reminded him that he was no longer a teenager. He did not say anything—just turned back to his thick book and his mug of coffee.

She had gone back inside then, found Dan, and told him to remind her to remind him that he had to get beer for the party. Dan had said, “What? I don’t understand.”

She took the ingredients out of the fridge and studied the newly created empty space on the shelves inside. She hoped there would be enough room for the beer that Dan was supposed to be getting.

“What kind should I get?” Dan had asked the night before while they got ready for bed.

“Keep your voice down,” she had said.

“He’s asleep.”

“You don’t know that. I keep noticing his light on later and later each night.

Have you seen that?”

“I think I remember seeing Coors at that tailgate I went to for his frat in the fall.”

“Ok.”

“So I’ll get Coors?”

“Sure.”

She bent down and turned on the oven and then she got to work mixing items in the bowl. First went the baking soda, followed by the baking powder, the eggs, milk, flour, cocoa, salt, and vanilla. Sweat formed on her brow as she stirred. The routine had not changed. The process had been the same for years. The ingredients always went into the bowl in that order. The cake always came out of the oven looking the same.

After pouring the mix into a pan and carefully placing it into the oven, she stood up and remembered there were still things to do. She ascended the stairs into her room. His presents were at the front of her and Dan’s bed. She fell into a seated position—surrounded on all sides by wrapping paper and scotch tape and the cardboard boxes from Amazon that she ordered.

“So things for the room?” she had asked.

“I guess,” he had said.

“No concert tickets? Video games? Clothes?”

“It’s ok. I’ve got enough money saved up from babysitting for the Goldman’s.” “Sweetheart, it’s your birthday. You know you can have whatever you want.

Don’t worry about money.”

“I promise,” he pulled his eyes from the television then, “all I need is a couple things for my room next year. The frat doesn’t supply a desk lamp or a fan or anything like that in the rooms. You have to bring your own.”

“Honey, it’s your birthday! Your 20th birthday no less! It’s not about what you need. It’s about what you want!”

His eyes fell back to the screen.

“All I want is a few things for the room.”

“Okay,” she had said.

“Thanks mom,” he had said.

With her left hand, she held the wrapping paper in place, and with her right, she tore off a piece of scotch tape. Carefully, she folded the wrapping paper over the bland, brown cardboard box that housed the alarm clock that she bought on sale. When she was finished, she reached for another cardboard box at the foot of her bed.

The doorbell rang as she was placing the final, wrapped present near the full- length mirror that leaned up against the wall in her room. As she left to go answer the door, she caught her reflection in the mirror—hiding behind the stack of presents in the corner of the frame. With a sudden flood of dread, she realized that

she could no longer remember which present was which. The stacked gifts were almost all identical in shape and size, suffocating in their cardboard boxes, and there, all reflecting the same image of the birthday cake and burning candles pattern across the glass, she realized there was no use trying to tell them apart. She sighed and recalled the struggles of trying to wrap the bicycle he got when he turned six. Oh well, she thought to herself, I’ll be as surprised as he his.

But then she remembered that she had purchased exactly what he had asked for.

The doorbell rang again and she hurriedly left her room and ran downstairs.

The kids pooled in the foyer once she opened the door. There were fifteen or so. Eight or nine boys. Six or seven girls. She remembered Don Stevens was now Dawn Stevens so she wasn’t sure how to correctly estimate the ratio of male to female. For all her talents, she wasn’t very socially aware.

The kids swayed in the hallway. She began detailing the plan. Ricky and Hunter would pick him up at the coffee shop in an hour and take him home. She said something along the lines of, “and then you all know the drill.” She laughed and the kids did not.

Dan came crashing into the front room. There was a silver can glued to his left hand. The silver cardboard case hung from his right.

“Hey kids!” he yelled. “Who needs a brew?”

The boys cheered and greeted Dan like an older brother. He handed out beers. She went into the kitchen and got the tray of crackers and vegetables and tortilla chips. Then she went into the den. The boys were surrounding Dan. The girls were in the corner—observing, laughing. All the boys had beers. A few of the girls did. She walked around the room, offering celery sticks and scoops of the guacamole she had prepared the day before with fresh avocadoes picked from their tree in the backyard. After making a full lap, exactly one piece of celery and four tortilla chips had been taken from her tray. As she was leaving the room, she heard Dan finishing a story about him getting too drunk in college and vomiting through a screen door. The boys erupted in laughter as she set the full tray down on the island in the kitchen.

She took the cake out of the oven and set it on the island next to the tray. She produced the cans of icing from the fridge. Like a painter, she carefully applied the icing to the cake in layers. In between coats, she licked her fingers and had a chip dipped in guacamole.

She heard a can hit the floor in the next room. She heard beer fizzle and burst and then she heard Dan yell, “Now you have to chug one!”

She watched Timmy Greenfield, who had played shortstop to her own son’s second base on the high school baseball team, run into the kitchen, throw open the fridge, and grab a beer. They made eye contact after he shut the door.

“Oh. Uh. Hi Mrs. Miller.”

“Hello Tim,” she said.

“Thanks for all this,” he said, “Rory’s gonna love it.” “Thank you, Tim.”

He nodded and left the room. She turned back to the cake and began to apply the final layer of icing. She heard Dan cheering and then the pop of a tab being pulled from a can. The cheering turned to chanting.

“Timm-y! Timm-y! Timm-y!”

She could hear Dan’s voice above the rest.

Out of the corner of her eye, she noticed two pairs of Chuck Taylor’s walking

up the stairs outside the kitchen. Two girls soon became visible to her. Rebecca Little and Tanya Jackson? That was her guess. The girls’ backs were to her. She stopped applying the icing and watched them as the girls fiddled in their purses. After a moment, she noticed a plume of smoke protrude from Rebecca’s lips. Then she saw a cigarette clutched between Tanya’s fingers. She wondered if she should go outside.

She was putting the last candle on the cake when the doorbell rang. She stood up.

“Everyone! Everyone!” She yelled above Dan’s voice, which was still echoing out above the boys’ laughter.

“Everyone! Places!”

She grabbed the bar-b-q lighter that she had made sure to leave on the island the night before and proceeded to light all twenty candles while Dan and the boys stumbled into the front room. With the candles lit, sending off bursts of smoke into the air, she carried the cake toward the door. On her way, she tapped the kitchen window with her free hand. Rebecca and Tanya spun around, fear freezing their faces in shock while smoke slowly poured from the corners of their lips. She waved to the two girls and mouthed, “he’s here.”

With that, she hurried into the front room.

“Okay,” she whispered, “everyone ready? He’s going to be so surprised!” She walked to the front door. She steadied the cake on her right hand like a

waitress and wrapped the fingers on her left hand around the doorknob. “Okay. 1…2…3!”

She threw open the door.

“SURPRISE!”

The yell fell out of the newfound opening and echoed through the valley.

In the doorway were Ricky and Hunter.

“Where’s Rory?” She finally asked.

“Hey, Mrs. Miller,” Ricky said.

“We’re sorry, Mrs. Miller,” Hunter said.

“What’s going on?” Dan yelled louder than he should have.

“Where’s Rory?” She asked again.

“He wouldn’t come,” said Ricky.

“What?”

“He said he knew what was going on as soon as he saw us at the coffee shop,” said Hunter.

“Yeah,” said Ricky, “and then he said he absolutely would not leave.” “Oh,” she said.

“We’re sorry Mrs. Miller,” said Ricky.

“We tried Mrs. Miller,” said Hunter, “we’re sorry.”

She backed away from the door.

“What the hell is going on?” Dan yelled.

She walked through the foyer, through the front room, past a bewildered group of her son’s old friends, and began to ascend the stairs with the cake still balanced on her right hand.

When she reached the top of the stairs, she heard Dan yell, “well more for us, right boys?”

Then she heard a cheer.

She opened the door to his room. A line of yellow material had hardened across the wood floor. She realized that it must have been egg. The yellow yolk that had soaked the wrapping paper through must have dripped onto the floor when she carried it to the trash. She sat on his bed. She looked out the window. A plume of smoke suddenly ran gray across her blue view of the sky. She set the cake down on the mattress and stood up and looked out the window. Rebecca and Tanya were in the same spot—unmoved—smoking cigarettes that looked full and new.

She pried her eyes away from the window. She sat down in his bed again and began to cry. She looked down at the floor, at the crusted egg yolk, and reminded herself she needed to clean it. She moved the birthday cake, chocolate on chocolate just the way he liked, from the mattress to his nightstand. She placed the plate on the thick book that sat there. Then she wiped her eyes, blew out the candles, and left the room.

Mothers

Leslie C. Lee

Apple rinds spiral

in time with the

slicing and the

crispness whispers

shuck, shuck

to the knife

which in apple-speak

I thought meant

“Ow, ow

Careful now.”

As my mother peels,

she turns the red-orange orb

naked, and it pales.

White, like the underside

of her slim wrists.

Most mothers tell

stories at bedtime

but my mother peels

and tells me

once

there was a woman with

a boy and husband

A poor woman,

she peeled the apples

that fell

from their only tree

she ate the thin, dry rinds

but gave her boy

the slices,

fresh and golden.

The son asked,

why do you eat only the peels?

She said, “Because

they are my favorite.”

He laughed

in response.

Then he grew rich, married,

and returned to his mother

with a present.

A loaded box

of tattered apple peels.

My mom’s hands,

nimble and slim

like bone,

her nails smooth

like sea-worn stones,

gather the spidery rinds

And she eats

the apple paper

that holds no juice

The skin, sour.

She eats.

The Edge of Arden

Haley Beasley

They lived their lives in a spinning wheel that never changed its speed. Slowly, always slowly—never going anywhere but around. Carefully, too. Not one word out of place, not one head of hair left un-brushed, no shoelace left untied.

Everything in Arden moved like clockwork. At dawn, the roosters at McGinnis’s farm would crow and croon until the last lazy soul dragged himself out of bed. By eight, the morning bell at Arden High rang, calling in the last few stragglers. Younger schoolchildren were at their desks, pencils ready by nine. At the end of the school day, kids were out in the streets—riding their bikes, playing hopscotch, trying to make something out of the long stretch of dust and dirt they called home. By six thirty, everyone was off at work and home with their families. Those without families made an early stop to the one and only bar in town where they relished in communion with other lone wolves. Children were in bed by eight.

Nobody was outside after ten thirty.

And nobody crossed the city lines—from the edge of the McGinnis farm to the north, to the old cotton mill to the south, and the long stretch of cracked asphalt that ran from east to west. Everybody stayed right where they were.

Every day waxed on in the exact same manner. Nothing happened too swiftly. No one sped up their plans. Even the outcasts and troublemakers of the town seemed to abide by the same set of rules. Everything was drawn out languidly, step by step, until the day ended. Then they’d begin again.

Kit’s heart didn’t beat slowly.

“How’s it feel?” asked Lena. She scooped up her son’s untouched plate of spaghetti and encased it in plastic wrap before popping it in the fridge with the flickering lights. It was an old fridge. It was an old house—passed down from generation to generation of the Loman line. Not the nicest house in Arden, sure. Nor did her late husband ever make an effort to dress it up a bit. His ancestors had lived in this house since the birth of the town. If it was good enough for them, it was good enough for him. And it was good enough for Lena. She made a mental note to get the lights in the fridge fixed, a note she forgot ten seconds later.

Kit drummed on the table with his fingertips, wrapped up by the book in his lap. He turned the pages swiftly; he ripped most of them. He read as if the words would fade if he didn’t catch them fast enough.

“Kit.”

“Huh?”

She washed her own plate in the sink, her back turned to him. “How’s it feel?”

“What?”

“To be a high school graduate?”

He could feel her proud smile, though he couldn’t see it. His fingers stopped drumming for a moment, but he never lifted his eyes from the book. He only had twenty pages left.

“Good.”

“What’d you say?”

“Feels good.”

“Good? That’s it? You know, you really should be proud. Graduating isn’t easy. I couldn’t do it. Your dad couldn’t do it. We got along all right afterwards, but it’s always a blessing to have an education. Don’t you think so, Kit?”

“Hmm?”

“Don’t you think it’s a blessing?”

“Uh huh.” Rip.

“Kit.”

“Hmm?”

“Kit, are you listening to a single word I’m saying?”

Kit clapped the book shut and lifted his gaze to his mother standing at attention with her hand on her hip.

“I don’t like it when you ignore me when I’m talking to you,” she said. “It’s rude and disrespectful. You’d think you’d have learned better—you’re an adult after all. And still, you don’t know how to talk to your mother.”

“Sorry,” but softly. He opened his book once more, hoping to breeze through the last dozen pages before she started off on another lecture.

“What’d you say? You know, I do hate it when you mumble. If I had a dime for every time I told you to speak properly . . . Cliff Walker talks so nicely—every word clear as crystal, and he’s got such a nice voice. I just wish you’d . . . you’d . . . what is that word. Starts with an E . . . Can’t put my finger on it, but, honestly, Kit—”

“Can’t I get some peace and quiet?” he snapped before hopping up from the table and darting into the next room.

Lena stood for a moment and waited for the shock to wear off. Then she wrung her hands together and stared at the chair where Kit had been sitting. She straightened it up, then cleared away the rest of his utensils.

He was always different from the other kids. When he was a boy, he would run to school. Ran so fast, he’d always trip and come home with ripped jeans and bloody elbows. The minute he got a car, he drove his truck so fast down Roanoke Road he got into three accidents before the month was out. He could never sit still or quietly—always rapping his knuckles on the church pew, or tapping his foot while waiting in line, or pacing back and forth. He got into fights. He talked back. Other children could stand still. Other children looked you in the eye when you talked to them—not at the sky or in a book.

Other children never got as close to the town line as Kit did. He’d go out there all the time, to the edge of Roanoke Road heading west. He’d sit right under the sign: Welcome to Arden. He’d sit there for hours, sometimes from noon to dusk. Oftentimes, he’d bring a book or a journal with him, scrawling in large, untamed script all the wonders of his imagination. Other children played sports or instruments.

All Lena wanted was for Kit to be like other children.

“Kit . . .” She made her way into the sitting room. He had finished his book and was staring out the window. A couple of kids from his high school were riding their bikes in circles home from the local diner, waving their caps above their heads with wide grins on their eager faces.

Kit stared at them with a seething bitterness that radiated off of his person.

“Kit . . .” Lena hovered in the doorway. “I’m sorry. I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to annoy you.”

He was silent.

“Please, talk to me,” she said. “I won’t say another thing. I’ll just listen.”

The silence stretched on to the ends of the earth. Lena parted her lips to break the quiet when Kit clapped his hands together, leaning forward on the couch.

“What happened to my father?”

Lena had no words for that question.

He looked at her with a pointedness that made her squirm. “Mom . . .”

“Your father?”

He laughed and it stung like a needle in the arm. “You never talk about him. No one talks about him. And don’t tell me he never existed.”

She stared at her palms.

“What?” His voice always had a biting edge to it, especially when he was angry. Which was more often than not these past few weeks. “Don’t tell me I’m a case of Immaculate Conception.” He cocked his head at her, leaning in. “Are you the Virgin Mary?”

“Don’t be ridiculous, Kit.” Her words floated from her lips like smoke from a cigarette. “He died when you were young.”

“Did he?”

“Yes. I don’t know why you keep pressing the issue. Now, you’d better get to bed. You know Mr. DeWitt wanted to see you tomorrow—to talk about getting a job at the garage. He knows you’re handy around cars; I mean, it practically runs in your blood. Your grandfather worked in that old garage till the day he died. He loved that place. And he would’ve loved to see you take over. If only he could see—”

“I talked to Sinclair today. While I was walking to school.”

Lena blinked twice before looking at him. “Why were you—”

“He told me something,” Kit said. He scratched the back of his head. “About Dad.”

Lena could feel the ice in her veins.

“He told me—”

“Kit, you can’t listen to a thing that man says,” said Lena. “He’s a crazy drunk that everybody just tolerates because they’re too nice to set him straight. Harmless old man, but a crazy drunk nonetheless. I can’t imagine what you were doing listening to—”

“He told me he saw Dad’s car heading west down Roanoke one night. Ten or eleven years ago.”

“Sinclair was seeing things . . .” Lena said it with a laugh. She hoped it didn’t sound forced. “Your father died when you were very young.”

“He remembered the license number. He remembered everything. He told me he watched the taillights till they disappeared on the horizon.”

Lena moved over to the couch. She placed a gentle hand on Kit’s knee. “Kit . . . Kit, look at me.”

His eyes were just like his father’s. Clear. Unflinching. Unashamed. She recoiled under that gaze.

“Your father died in his sleep,” she said. “Don’t you remember the funeral?”

“I don’t know. I don’t know.”

“Everybody from town came,” she said.

“They did?”

“They did.” She stroked his brown hair, reassuring that part of him retaining some logic, scattering away the doubt with a sad smile. “Don’t you remember the police coming in and carrying his body away?”

Kit cocked his head slightly. “I keep trying to remember that. I keep trying to remember something solid I saw. Something that reassures me without a doubt that he’s dead and buried over at the cemetery.”

Lena dropped her hand.

“I can’t,” he said. “It’s this . . . this feeling that keeps itching at me. Where’s his car, Mom? Where’s his car?”

“I sold it,” she said. “I couldn’t bear to keep it.”

“If you couldn’t keep the car he drove, then how can you sleep in the bed he died in?”

She latched onto Kit the way you latch onto the railing of a staircase when you begin to slip on a step.

“Why can’t you just be happy here and now?” she asked. She tried to calm herself for fear of sounding insane, but the fear spread inside her. “Just go see Mr. Dewitt in the morning. Go to the diner with your friends. Stop sitting around and sulking and reading those books and . . . and thinking about things you shouldn’t think about.”

Kit’s face contorted into challenging confusion. “Like Dad?”

“Like the past. Start thinking about your future, Kit!”

“I have.” He broke away from her grip with ease. Lena sat there, staring at him, like she didn’t even know him. When did he grow up? When did he stop being her little baby who’d cry non-stop when he wanted to be picked up? When did he get strong enough to get out of her grip with little more than a gentle push?

Kit clasped his hands together.

“I thought about my future. I thought about leaving and staying here. I mapped out what would happen if I stayed. I’d work at the garage and marry Cassie from down the street and live in this old house and spend the rest of my days making you and everybody else in this town happy.”

That’s when the grin hit his face. It was a toxic smile, the kind filled with unadulterated ambition.

“And then I thought, what if I left? What if I could make it out there? I’ve never given myself the chance to try my luck in the real world.”

“Kit, this is—”

“This isn’t the real world,” he said, the bitterness drawing back into his voice. “This town is an infinite hourglass. It’s like a book with the same story and the same plot, but the cast of characters is always changing—like those TV shows that follow the lives of the original casts’ children and their children and their children. This town makes me want to put a bullet through my skull.”

“Kit!”

“So like I said, I thought about it. And I prayed a little.” The toxic grin returned. “I decided to leave. I just have to decide where to go.”

Lena felt like her world was fading around her. And it was. Kit was her world and here he was, revealing plans to leave her all alone.

Just like his father.

He didn’t know what that meant. He didn’t know the danger. He didn’t know what that would do to her. She couldn’t think of anything to say to him.

“Kit,” she started. “Why don’t . . . well, why don’t you wait? Spend a couple of years in the garage? Save up your money. And then, if you decide that you’d really like to go to school, well, you can take some classes online—just to get your feet wet. Or you could try another job in town—if the garage doesn’t suit you. And then maybe, maybe, if after all that time you still want to go, well, then we can talk about it then.”

“If I don’t get out now, I’ll never leave.”

Lena laughed while trying not to cry. She was growing desperate. “Why do you sound like you’re a prisoner? Is it so bad here?”

Kit wrung his hands. She could see the internal struggle going on inside him. She understood that this decision wasn’t easy for him—and that brought her joy and a glimpse of hope.

“It’s not hard for you . . .” he said, “You love this.” He gestured to the house. “You love getting up in the morning extra early to make me breakfast, heading to the florist, making everyone’s day better with your bouquets and your words of wisdom, and then coming home early so I’ve got dinner by the time I’ve gotten back. You love everything about Arden—the people, the monotony . . . no, the . . . predictability of it all. Everything is comfortable here and that makes you happy.”

He met her eyes. This time, she held his gaze.

“That’s never been enough for me.” He leapt up to his feet and began pacing. “You know what everyone else thinks about when they look out west past the welcome sign? Nothing. A road going nowhere. I see an uncharted world. A world to be explored. I see a never-ending adventure of excitement and opportunity and—”

“It’s not out there, Kit. It’s not out there. It’s all a lie.”

“Am I supposed to take your word for it!” His voice bounced off the walls now. She hated it when he shouted. She liked it better when his words were soft and cold, then loud and searing. “What have you ever done—what has anyone in this town ever done that’s brave? Or uncomfortable? No one here asks questions, no one thinks for themselves. It’s like being stuck in a twisted, totalitarian world with some omniscient tyrant doling out orders left and right. Do what your father did and his father did and his father did. Don’t leave town. Don’t ask questions. Don’t say things that make people uncomfortable. Don’t look at people the wrong way. Never say the wrong thing. Never do things too quickly. Never make any damned decisions on your own.”

He gave her an accusatory look. “But there’s no tyrant. It’s just you. And Cassie. And Mr. Dewitt. And everyone else in this God-forsaken town—you suppress yourselves. You don’t need some dictator sucking the life and imagination and wonder out of the world. You do it to yourselves.”

“There isn’t anything out there, Kit.” Lena could see her argument slipping through her fingers. He stopped pacing. For a moment, he looked calm—almost serene. But his eyes burned with a determination that made her fear spread.

“I plan to find out for myself,” he said.

A tear slid down Lena’s cheek. She was losing him. She was losing him. “What about me?” Her voice sounded small and infinitesimal against his. She spoke louder. “What about me? You’re going to leave me here all alone?”

“That isn’t fair.”

“Surprise! Life isn’t fair, Kit! You think I dreamed of doing this, becoming this when I was younger? You think I wanted this life?”

“I think you never dreamed of something more.”

“Everyone has dreams, Kit.” She sighed. “People in this town are just more realistic. I don’t want you to get hurt.”

He looked disgusted. “You aren’t thinking about me. This is about you.”

“I just . . . I don’t want you to leave me.” The tears came freely now. She spoke from a dark place deep within herself, twisted with fears that had built up over a lifetime, converging all in this moment. “Don’t leave me like your father left me.”

Kit knelt before her. He took her small hands in his.

“I think that’s exactly what happened.” His eyes searched her own. She hated his stare. She felt transparent when he stared at her.